As social media becomes increasingly integrated into our everyday lives, it influences simple elements of our daily routine such as the clothes we wear. Today’s current fashion sphere is more connected than ever before thanks to social media, as Autumn Wilberg explains, “fashion is more fluid and interactive than ever before – changing the way fashion brands connect with their core audience” (Wilberg, A. 2018). Another way of describing connecting with the core audience is networking. Networking in any area of work is necessary but particularly prominent within the fashion industry as it is vital for career progression, reputation management and audience engagement (Gregg, 2011 p.13). However, navigating audiences can be a difficult task and lack of control over how content, such as fashion marketing campaigns/promotions, flow through social media can result in “disclosures that travel beyond the imagined audience”, occasionally causing serious complications (Quinn, K. and Papacharissi, Z. 2018, p. 361). An example of this is the fashion company Sunny Co. Clothing campaign in 2017 promoting a Baywatch-themed swimsuit. The clothing line announced through Instagram that any individual who reposted and tagged their swimsuit picture on their own social media account within the first 24 hours would receive a free $64.99 swimsuit. The promotion went viral and resulted in the company not being able to keep their promise and forcing them to cap the promotion leaving customers outraged. The incident has been debated by consumers and commentators with the overarching conclusion being that the promotion was a scam and a ‘social media fail’.

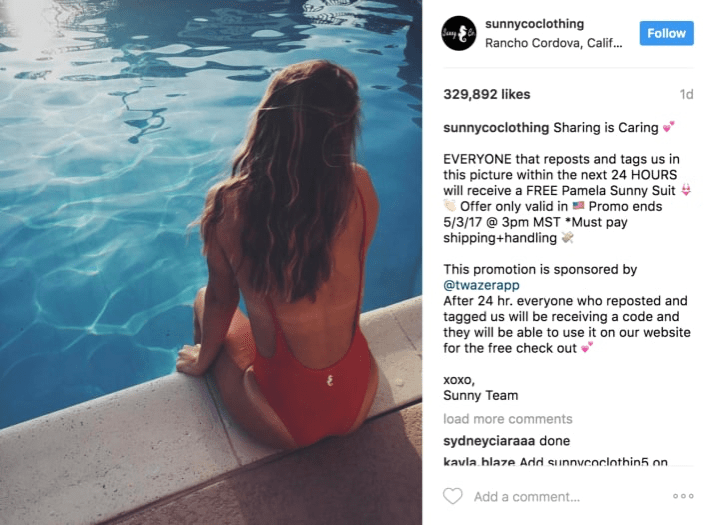

The Sunny Co. Clothing line was created by two students, Alan Alchalel and Brady Silverwood, who were both seniors attending the University of Arizona at the time of the viral promotion. In May of 2017 the team announced on their Sunny Co. Clothing Instagram account a promotion of their titled ‘Pamela Sunny Suit’ inspired by the hit TV series Baywatch. The contest idea originally sought to generate engagement for their Instagram account, posting an image of a model wearing the swimsuit with the instructions of the promotion in the description.

The description read, “EVERYONE that reposts and tags us in this picture within the next 24 HOURS will receive a FREE Pamela Sunny Suit Offer only valid in US Promo ends 5/3/17 @ 3pm MST *Must pay shipping + handling* This promotion is sponsored by @twazerapp After 24 hr. everyone who reposted and tagged us will be receiving a code and they will be able to use it on our website for the free check out” (Fratella, D. 2017). The post also declared that for every picture shared with the hashtag #sunnycares a $1 donation would be made to an Alzheimer’s foundation. The promotion went viral within a few hours of it being posted, garnering over 346,000 shares and tags. The Sunny Co. Company quickly decided to end the promotion marking the swimsuits as ‘sold out’ on their website and stating that they had the right to cap it due to “the viral volume of participants” (Gollin, M. 2019).

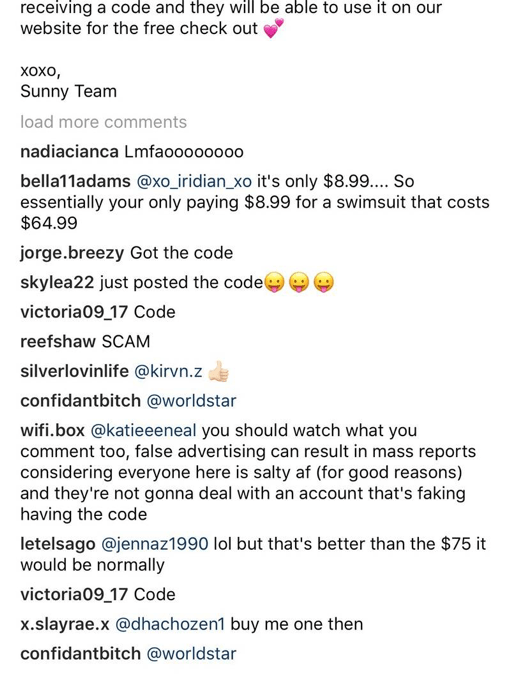

After the incident customers began angrily flooding the company’s social media accounts and the company directors private Facebook accounts with complaints and demanding refunds for shipping costs but reportedly none received a reply. People began labelling the promotion as a fraud and a marketing scam, going to extremes like threatening the company. Some women reported that even though they purchased the swimsuit using the promo code they were still charged full price for the swimsuit. Others claimed that when they went to purchase the swimsuit on the website they were being charged an extra $1 that was not donated to charity by Sunny Co. Clothing.

The primary contributing factor of this ‘social media fail’ is a term called the connectivity conundrum, which means a common discourse where social media assists to connect individuals and share information. When content promotions like the Sunny Co. swimsuit was first posted it quickly gained attention with individuals sharing the post, resulting in the company not being able to manage the flood of mass audiences and inevitably losing control over the situation (Graham, T, Dr. 2019). While some, like Justin Kelsey from the Medium Corporation argue that this promotion was a marketing ploy to gain attraction and was actually a success, a discussion of ethics arises on whether their marketing tactics were unethical and in bad taste. Through integrating the popular Baywatch ideology into their promotional swimsuits Sunny Co. Clothing leverages off that particular ‘aesthetic” and people become immediately engaged with that specific ‘look’. To boost their social status and adopt self-consciously constructed personas into their products the Sunny Co. company were able to market themselves taking advantage of contemporary consumer capitalism and gain “visibility and attention” (Marwick, A. 2013 p. 5).

Due to the nature of the promotion, the content spread through the Instagram platform, enabling fast distribution and reappropriation of content. The spreadability of the post was extreme and the technical affordances of the Instagram account made it easier to circulate the content at a high pace (Green and Jenkins, 2011, p. 112).

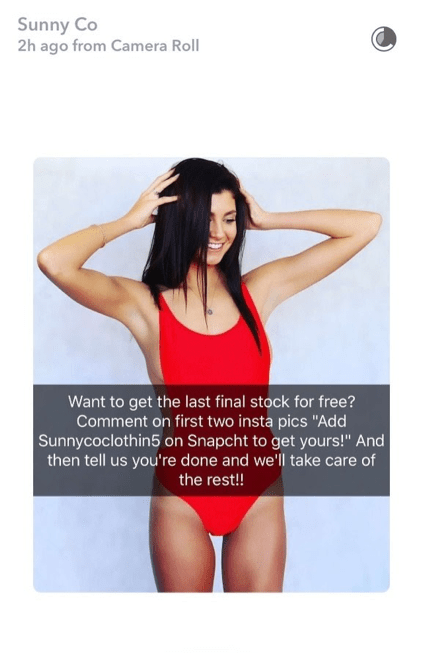

This was another key factor in this ‘social media fail’ as the viral nature of the promotion saw other platforms such as Twitter and Snapchat become involved in the giveaway. Multiple Twitter accounts renowned for stealing tweets posted the promotion, as well as a number of copycat Snapchat accounts requesting people to follow an unknown Sunny Co. snapchat page. This caused problems not only for the company’s reputation but to the impressionable younger demographic that were interested in this product. The wider social media coverage ultimately secured the Sunny Co. Clothing line over 750,000 followers and its questionable intentions were deduced by most as a promotional masquerade and false advertising. The backlash was severe, consequentially leading the company to temporarily delete their Instagram account and put out a statement of apology explaining that they simply weren’t capable of producing orders of such a large quantity and “promising to send all the promotions’ participants their bathing suits and refund the suits of those who had to pay” (Nast, C. 2017).

This social media fail was a poorly thought out marketing campaign that severely backfired on a company who did not take into consideration the full repercussions of their marketing promotion and did not understand Instagram’s algorithms and user connectivity. The media strategy was effective in increasing the number of followers, however the failure was not limiting the scope of the promotion. If I was in charge of this media strategy for this organisation I would have focused attention on limiting the promotion to a level that allowed the company to fufill its obligations. I would have marketed the promotion as, the first 100 people to repost and tag the Sunny Co. Clothing Instagram account will win a FREE Pamela swimsuit plus pay for shipping and handling. For the next week anyone else who reposts and tags the Sunny Co. Clothing swimsuit will get a 25% discount on the full price of the swimsuit plus shipping and handling. This strategy will still increase the number of followers for the fashion Instagram account but it would be more pracitcal in terms of the company being able to produce and distribute the swimsuits.

References:

Fratella, D. 2017. Swimsuit company racks up 750,000 followers, makes small fortune from ‘giveaway’ – Social Blade. Retrieved from: https://socialblade.com/blog/swimsuit-company-sunny-co-clothing-viral-marketing/

Gollin, M. 2019. 15 of the Worst Instagram Marketing Mistakes by Companies. | Falcon.io. Retrieved from: https://www.falcon.io/insights-hub/topics/social-media-strategy/15-brands-most-embarrassing-instagram-marketing-mistakes/

Graham, T, Dr. 2019. KCB206 Social Media, Self & Society Week 11: New Media Ethics, Divides, & Non-Participation [Lecture recording] Retrieved from: https://echo360.org.au/lesson/080f8193-6704-4501-9540-bd6174aea94f/classroom#sortDirection=desc

Green, J., and Jenkins, H. 2011. “Spreadable Media. How Audiences Create Value and Meaning in a Networked Economy.” In The Handbook of Media Audiences edited by Virginia Nightingale, p, 112. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gregg, M. 2011. On Call. In Work’s Intimacy. Cambridge: Polity. p.13

Marwick, A. 2013. “Introduction.” In Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity and Branding in the Digital Age, 1-19. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p.5

Nast, C. 2017. People Are Actually Getting Those Red Swimsuits That Went Viral on Instagram. Retrieved from: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/sunny-co-clothing-bathing-suits-ship

Quinn, K. and Papacharissi, Z. 2018. Our networked selves: Personal connection and relational maintenance in social media use. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick, and T. Poell,(eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London: SAGE. p. 361

Wilberg, A. 2018. How Social Media and its Influencers are Driving Fashion. Retrieved from: https://digitalmarketingmagazine.co.uk/social-media-marketing/how-social-media-and-its-influencers-are-driving-fashion/4871